The ATO have adopted a firm approach to debt collection in recent years. Particularly in the SME space, there has been a surge in ATO debt recovery activity, including the use of garnishee notices, director penalty notices and applications to wind up companies.

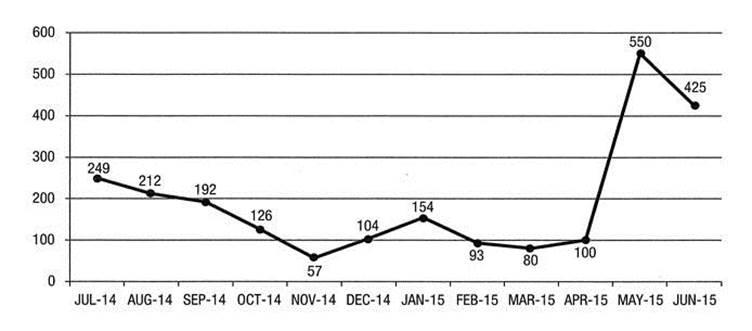

The graph below shows the number of applications brought by the ATO in the 2014-15 financial year, and demonstrates the current approach being taken by the ATO:

As shown above, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of winding-up applications filed by the ATO against companies. Since April 2015, the number of ATO wind-up applications have been above 300 per month. This is well above the ATO’s long-term average of approximately 90 per month.

In the past, the ATO would usually have waited for a company’s debt to reach around $300,000 plus before taking action. However, the new level for winding up proceedings is more like $90,000 to $100,000, a significant drop. The ATO is also seeking third-party property as security for repayment agreements.

Before the ATO takes drastic measures such as applying to wind up a company who has defaulted in its obligations to pay tax, it will ordinarily be open to entering into some form of payment arrangement with the company, subject to the company meeting certain criteria.

On the one hand, an early resolution of an outstanding tax issue by entry into a payment plan may benefit the company as it is appears less costly than having to deal with other forms of debt recovery and it may allow the company to continue trading.

In a review of the ATO’s debt recovery practices carried out by the Inspector-General of Taxation in July 2015, the Inspector General formed the view that the ATO has a role to support the broader economy in terms of the impact of its actions on third party creditors. Further, the Inspector General recommended that the ATO ought to take earlier, more frequent and proportionate debt recovery action to minimise the necessity to take firmer action at a later time and to prompt company directors to address impending insolvency. The entry into payment plans is a good example of where the ATO may seek to achieve these purposes.

Security for payment plans

In addition to entering into a payment plan, the ATO may require that the company or its directors provide security for the performance of the company’s obligations under the payment plan. In its review of the ATO’s debt recovery practices, the Inspector General has stated that in deciding whether to take or require security to be provided against the assets of a taxpayer or third party in relation to existing debts or future tax liabilities, the ATO may have regard to, amongst others, the following considerations:

- the quantum of the debt;

- the period of time the debt has been outstanding;

- the taxpayer’s ability to pay, including its other liabilities and arrangements made by other creditors to secure their debts;

- the taxpayer’s compliance history; and

- the nature of the security being offered.

The Inspector General has acknowledged that the security to be provided may take any number of forms, but the ATO prefers a registered mortgage from the taxpayer or a third party over freehold real property where there is sufficient equity in the property or an unconditional bank guarantee from an Australian bank. The ATO is also known to enter into equitable or caveat mortgages with taxpayers and third parties in its favour to secure debt that is owed to it.

Unfair preferences – the sting in the tail

A further issue that is rarely considered by company directors before entering into an arrangement with the ATO, or before making payments to the ATO generally to repay the company’s tax debt, is their potential personal liability in relation to payments made under such an arrangement in the event that the company subsequently goes into liquidation.

If a company in liquidation has made payments to the ATO in the 6 months prior to the relevant relation-back day (usually the date of liquidation) in preference to other creditors of the company, it is likely that the liquidator will have a claim against the ATO for a preference under s 588FA of the Corporations Act. That is, a claim that the transactions gave rise to the ATO receiving from the company more than the ATO would receive from the company if the transactions were set aside and the ATO were to prove for the tax debt in the winding up of the company. If the Court finds that the payments to the ATO constituted unfair preferences, it is likely that a Court will make any order under s 588FF of the Act requiring the ATO to pay back an amount equal to the payments made.

The sting in the tail is if the ATO is ordered to repay an amount under s 588FF, the directors will be personally liable under s588FGA to indemnify the ATO against any loss or damage resulting from such order. That section relevantly provides:

- “Each person who was a director of the company when the payment was made is liable to indemnify the Commissioner in respect of any loss or damage resulting from the order.”

- “The Court may, in the proceedings in which it made the order against the Commissioner, order a person to pay to the Commissioner an amount payable by the person under subsection (2).”

The director’s liability under s 588FGA will arise at the point when the Court makes an order against the ATO under s 588FF. Therefore, the liquidator will need to first commence proceedings against the ATO and obtain the relevant order against the ATO before the director’s personal liability arises.

It is open to the ATO to join the director to the proceedings commenced by the liquidator against the ATO for purposes of enforcing any potential liability under s588FGA, should an order be made against the ATO. In those circumstances, the directors have a right to be heard on the primary dispute between the ATO and the liquidator.

When personal liability bites

The potential personal liability may come as quite a surprise to a director who has caused his or her company to make payments to ATO under a payment plan with the best intentions of reducing the company’s tax liability, or alternatively where the company has had no choice but to make payments to the ATO pursuant to a garnishee notice.

A company may be two thirds of the way through its payment plan when it hits the wall and goes into liquidation. In that scenario, it is more likely than not that the ATO will have to repay to the liquidator any instalments made under the payment plan within 6 months of the relation-back day. The ATO will then have a claim against the directors under the indemnity referred to in s 588FGA noted above.

The ultimate result may be that directors become personally liable for the tax obligations of the company when they would not otherwise have been liable, such as for GST. This issue may result in a company’s business risk effectively becoming a director’s personal risk, thus exposing the director’s personal assets including the family home.

In view of these risks, it is even more important that, prior to entering into any payment plan or arrangement with the ATO, directors have the confidence that the company will be able to meet its obligations under such arrangement right through to the end. Extreme action, such as a winding up application, is usually only taken by the ATO when there has been a failure to engage in relation to a debt or when there has been consistent failure to comply with obligations under a payment arrangement.

To manage the risks identified above, it is crucial that directors take sound professional advice at an early stage.

Disclaimer

This information is provided as a guide only and is not intended to constitute advice whether legal or professional. You should obtain appropriate advice concerning your particular circumstances.

** Information current as at publishing date.